Native Deodorant

In the course Research for Consumer Insights at NYU, I worked with a team to answer the question: Are consumers more likely to purchase deodorant from brands focused on sustainability or effectiveness? Furthermore, does a brand focusing on sustainability sacrifice its reputation in the consumer’s mind?

Methodology

Our team began our initial preliminary research by conducting two 45-minute-long focus groups of college students. These initial focus groups were relatively small with 10 participants in the first group and 11 participants in the second group. Through these focus groups we found that participants mostly chose their deodorant based on smell, cost, habit, and lasting time. We also discovered there was a clear divide between environmentally conscious consumers and those who are not. Based on our preliminary research findings, we came up with a new hypothesis to test: if Native wants to expand their consumer base, then they should highlight the effectiveness of their products in advertisements more than the environmental and health implications of their deodorant.

Secondary Research

Our secondary research method was a survey of approximately twenty questions followed by a short 2x2 factorial experiment. We broke the survey potion into two parts, the first part was to find out if sustainability mattered to consumers’ purchasing choices. The second part of the survey asked questions related to general deodorant preferences, knowledge about sustainable deodorant, and further, if they are willing to pay more for sustainable deodorant. We revised three versions of our survey in order to validate our questions by providing more clarity to ensure that we would derive the correct data needed for the analysis. We chose to conduct a survey because it allowed us to reach unbiased opinions through anonymous answers. This was crucial especially if our first research focus group reached false conclusions due to factors such as groupthink and the speaking-up dilemma. We ended our survey and experiment after reaching a sample size of 79 completed responses because we felt confident that would be enough data to analyze. Our sampling plan prominently consisted of NYU classmates from this course and our other courses, as well as some non-NYU affiliated friends.

Experiment

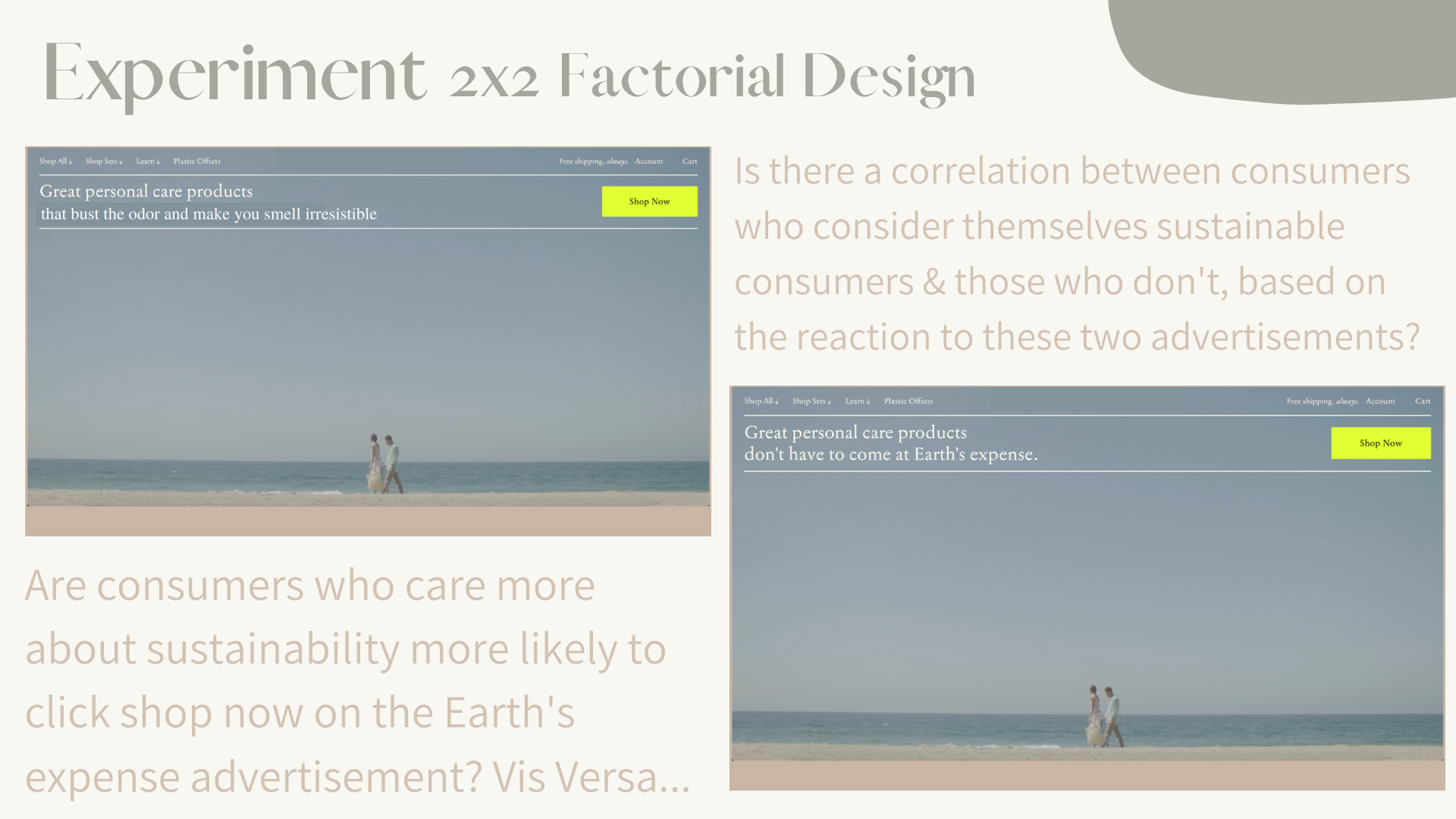

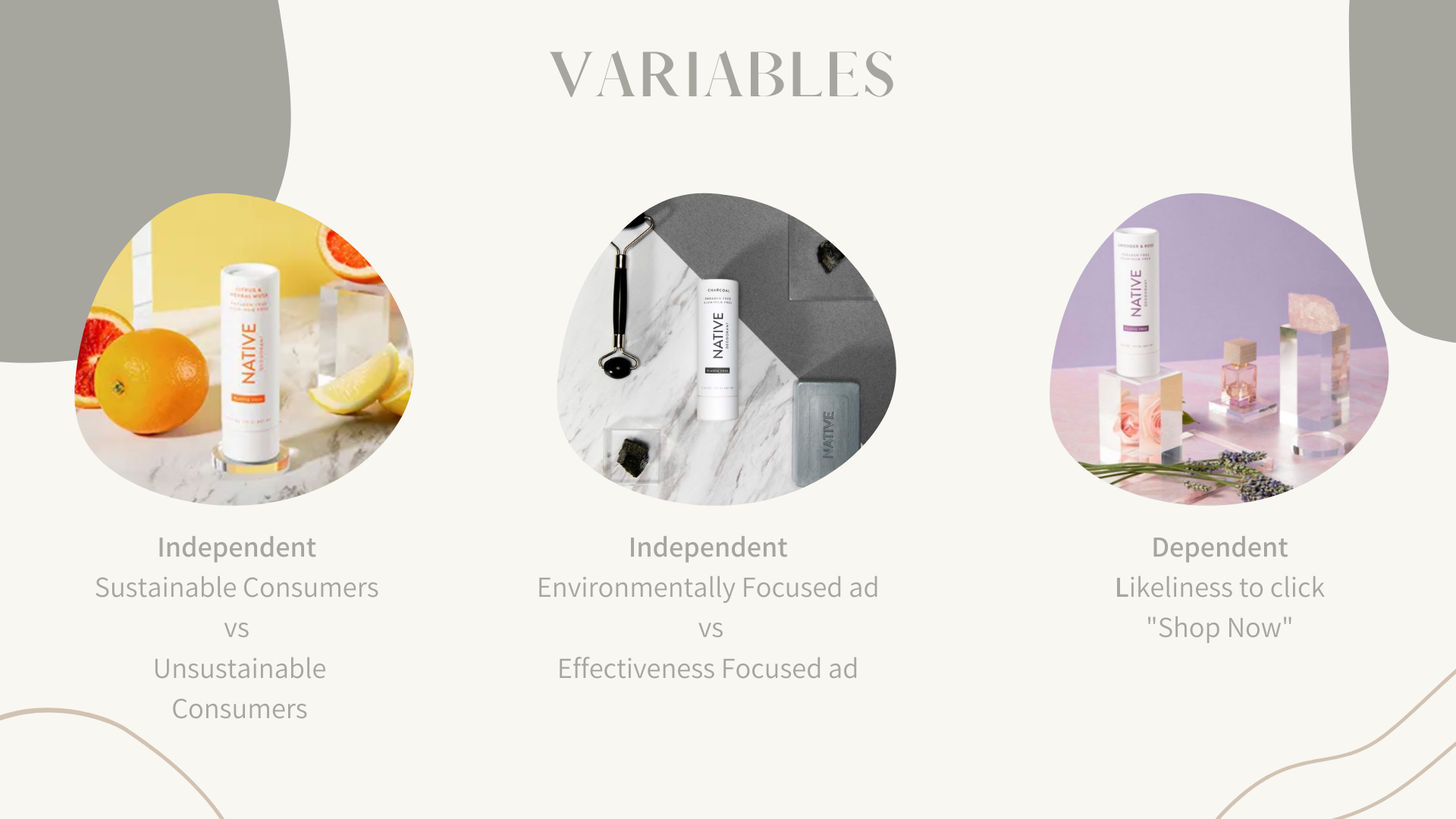

The experimental part of our survey randomly assigned participants to one of two advertisements. These advisements looked identical, but their message differed, where one ad used words catering to the deodorant’s effectiveness, and the other catered to the deodorant’s environmental impact. The first independent variable was the classified sustainable consumers vs. unsustainable consumers. The second independent variable was the environmentally focused ad vs. the effectiveness focused ad. The dependent variable was the likeliness for participants to click the “shop now” button. Through this experiment we wanted to see if consumers who cared more about sustainability were thus more likely to click “shop now” on the environmentally focused ad, and vice versa. Furthermore, our group wanted to test to see if there was a correlation between participants who considered themselves sustainable consumers and those who don’t, based on their reaction to the two advertisements.

Results

Sustainability Scores

In order to score respondents on a “sustainable consumption” index we asked respondents to state their level of agreement to two statements:

“The environmental impact of my purchases is very important to me”

“I identify as an environmentally conscious consumer”

Sustainable & Unsustainable

After re-coding these respondents into two groups (sustainable consumers and unsustainable consumers) we were able to have a better understanding of how consumers’ purchasing patterns affected their opinions throughout the survey. We grouped participants who have a 7 or below as unsustainable consumers because in order to receive a 7, they would have had to have chosen a combination of a 3 and a 4, a neutral and a slightly agree, to the above questions, or a 2 and 5, slightly disagree and strongly agree (a rare combination). While for participants who have a 8 or above, they are considered to be sustainable consumers. With this new recoding, we can see that 33 respondents are considered to be unsustainable consumers while 46 are considered to be sustainable consumers

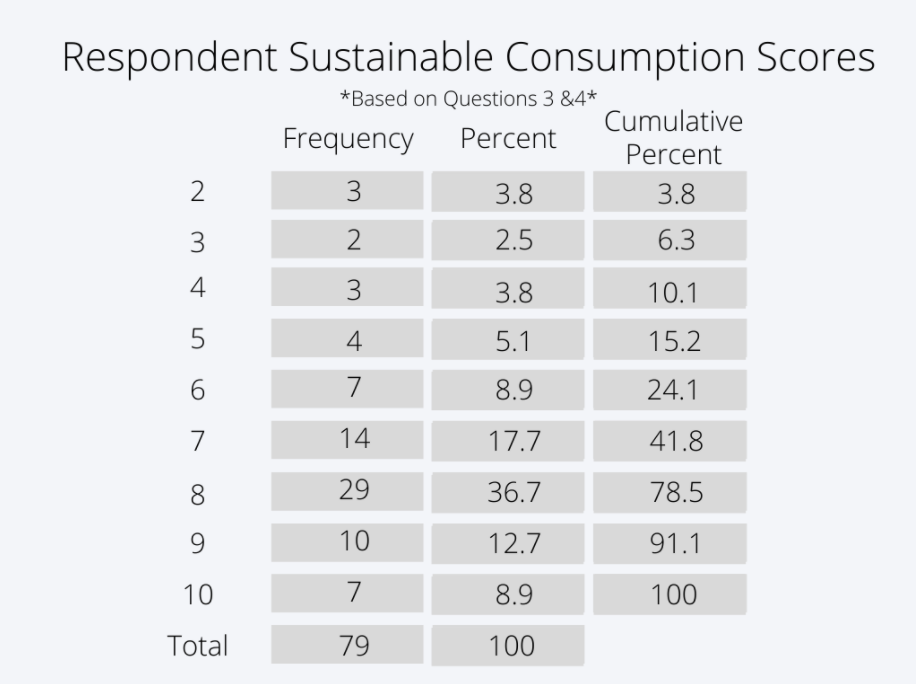

Scores

From the table, we can see that 41.8 percent of the respondents scored a 7 or below, which means the participants are relatively diverse in terms of their consumption behavior in relation to sustainability. It is also apparent that participants who scored 7, 8, 9 are 17.7%, 36.7%, and 12.7% of all respondents, respectively. This means that 67.1% of the respondents are in these three categories, meaning that most respondents are somewhat sustainable and less respondents are on the extreme ends of the spectrum. We used these two groups of consumers as one of the two factors in our experimental analysis.

2x2 Factorial Experiment Analysis Findings

In our experiment we showed half of the respondents the deodorant ad focusing on sustainability and half focusing on effectiveness. There were 39 participants who saw the sustainable ad and 40 participants who saw the effectiveness ad.

Non-Sustainable Consumers

When “non-sustainable” conumers saw the sustainable ad, their likelihood of clicking on “shop now” was 4 out of 5, while when they saw the effectiveness ad, their likelihood of clicking on “shop now” was 3 out of 5. This means that non-sustainable consumers were more likely to click on the “shop now” button when they saw the sustainable ad than when they saw the effectiveness ad. This could mean that even though these participants are not sustainable consumers, they still desire to shop more sustainably, think about sustainability subconsciously when making purchase decisions, or there is another factor that we did not consider. This also suggests that our assumption of non-sustainable consumers would value effectiveness in deodorant more than sustainability is not accurate.

Sustainable Consumers

When “sustainable consumers” saw the sustainable ad, their likelihood of clicking on “shop now” was 3.360, while when they saw the effectiveness ad, their likelihood of clicking on “shop now” was 3.476. This means that in our sample, interestingly, consumers who considered themselves to be sustainable consumers actually leaned towards the effectiveness ad. However with such a small sample size and such a small difference in likelihood to click “shop now” on the two advertisements, we cannot say that this result was statistically significant. From this experiment, the only thing really safe to say is that sustainable consumers, no matter which ad they saw, were not significantly more or less likely to click on “shop now” on the effectiveness ad or the sustainability ad. There could also be a ceiling effect happening here that sustainable consumers are already likely to click on the “shop now” button so the ad did not really have an influence on their decision making.

Sustainability vs Effectiveness

We also ran a frequency analysis on Question 13, which asked participants to select their degree of agreement with the statement “Sustainable/natural deodorant is more effective than traditional/unsustainable deodorant.” This was to get a better understanding of whether or not sustainability and effectiveness are mutually exclusive in the eyes of consumers, or if there even is a correlation between the two at all.

From the chart, we can see that 41 participants selected neutral and 23 participants selected somewhat disagree, while other choices each had 5 participants make the selection (Chart 3). This means that most participants think sustainable deodorant has the same effectiveness as traditional deodorant, which was also surprising to us considering our entire research study being centered around the idea that consumers see effectiveness and sustainability as differentiated from one another. Only 23 out of 79 participants (about ⅓) think that sustainable deodorants are somewhat less effective than traditional deodorant.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this research, we hypothesized that consumers would be more likely to purchase deodorant from a company that focused on effectiveness rather than the sustainability or environmental impact of the deodorant. From the analysis we ran, this was not so clear cut. As previously mentioned, consumers who did not identify as sustainable consumers were actually more likely to click “shop now” on the advertisement focused on sustainability than the consumers who did consider themselves sustainable consumers. Within the subset of consumers not considering themselves sustainable consumers, our hypothesis was proven incorrect, and ironically within the subset of sustainable consumers, our hypothesis was actually proven correct. From this survey, further research that could prove helpful to deodorant companies would be to study the different styles of deodorant advertisements to tap into a more emotional or subconscious appeal of advertising. For Native specifically, since non-sustainable consumers seem to be more interested in the sustainable advertisement, we recommend that the company can keep their current advertising on sustainable deodorant, but try to reach consumers who are considered unsustainable for a greater effect.

Limitations

We aimed to collect a comprehensive group of respondents that represents the general population, but those who completed our survey likely did not. As college students our easiest avenue of reaching out to potential participants was sending our survey to the students in our classes. While we didn’t ask participants if they were college students, we collected responses by sending out the survey via NYU classes, so it is safe to assume that the majority of respondents were NYU students as well. The majority of participants were ages 19-23, which is not an accurate representation of the total population, and likely not parallel with the entire population’s opinions and purchasing patterns. For example, Generation Z is much more likely to be concerned with sustainability and social issues. Of our respondents, 67% were, or at least considered themselves, “somewhat sustainable,” which is likely not representative of the total population.

Beyond the concept of age, is that these respondents represent an educated, and likely wealthier portion of the population than the general U.S. citizen. Educated individuals are likely to be more informed on the effects of sustainable vs unsustainable products, the harms of overuse of plastic in today’s economy, and the idea of sustainability in general. For example, a few respondents did not even fully understand what sustainability meant, or at least not in terms of deodorant. We attempted to address this by adding a definition of sustainability at the beginning of our survey, but really should have added a definition of sustainable deodorant to give respondents a more clear understanding of what the survey was really about, to help them understand what “natural deodorant” even means.

Despite these limitations we would like to think our survey can be generalized beyond simply a wealthy, educated and Generation Z subset of our population. We were able to ask family, parents, grandparents etc. who potentially rounded out the results by including some different groups of the population.

In terms of the actual experiment conducted, something to consider is the similarity of the advertisements shown to respondents. We were weary to have two advertisements that were too different from each other, so as to eliminate other variables, but looking back on the results, we probably should have made the sustainable deodorant advertisement more differentiated from the effectiveness advertisement. Both advertisements featured a beachy scene, and a “green” or “eco-conscious” feel to them. The only differentiator were the actual words, one claiming great “deodorant doesn’t need to come at the expense of Earth” and the other claiming to “Bust Odor. Smell Irresistible.” It is possible that simply the aesthetic of an “earthy” brand may have swayed the respondents' likeliness to click “shop now.”